--------------------

We find this discussion interesting in that there are always those who are looking for ways to label people. Too often those labels are used dismissively. It's easier to brand someone as a part of "***" so as to categorize them, either "us" or "them." "Them" are heretics and kooks, "us" are the ones with the correct doctrine. "Them" aren't saved and are false teachers, while "us" are the defenders of the faith, the ones who hold to the truth.

This desire to label results in awkward terminology like what manifests in this article. "Pentecostal" gives way to "Spirit-filled," charismatic," "renewalist," "Spirit-empowered," "New Apostolic Reformation," and "Word of Faith." Or one the author doesn't mention, "continuationist."

The discussion is also interesting in that it focuses on the "supernatural practices" side. There is no attempt to parse terminology for the "non-supernatural" churches, yet their practices and doctrines are probably just as varied.

We personally don't know anyone who is concerned about properly labeling what theological camp others are in. Generally, we believe anyone who has repented and has believed Jesus is Lord and received new life in Christ is in "our" camp. Or more precisely, are in God's camp. Beyond that, we don't feel burdened to be Doctrinal Police.

We personally don't know anyone who is concerned about properly labeling what theological camp others are in. Generally, we believe anyone who has repented and has believed Jesus is Lord and received new life in Christ is in "our" camp. Or more precisely, are in God's camp. Beyond that, we don't feel burdened to be Doctrinal Police.

Except of course when they start labeling. We then undertake to examine what they write and evaluate it according to Scripture. If their presentation is thoughtful and biblically-based, we will consider its validity and respond in kind. If it is disrespectful, we will also note that.

So what are we to make of these various groups of Christians? They are not a single denomination, despite the desire of some to pigeonhole them. There are some overlapping doctrines, but there are a lot of differences. Should we look for a new name to call them?

We would suggest that there is really no reason to separate out a category of Christians simply because they believe in the supernatural activities of God in the Church. We believe it could be a convenient excuse to engage in a form of bigotry. Too many Christians are focused on shades of doctrine to the exclusion of loving one's brother in Christ.

-------------

So what are we to make of these various groups of Christians? They are not a single denomination, despite the desire of some to pigeonhole them. There are some overlapping doctrines, but there are a lot of differences. Should we look for a new name to call them?

We would suggest that there is really no reason to separate out a category of Christians simply because they believe in the supernatural activities of God in the Church. We believe it could be a convenient excuse to engage in a form of bigotry. Too many Christians are focused on shades of doctrine to the exclusion of loving one's brother in Christ.

-------------

Todd Johnson, co-director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, couldn’t quite place the Chinese Christians he met at a conference in South Africa. Theologically, they seemed Pentecostal, so he asked.

They responded: “Absolutely not.”

“Do you speak in tongues?” Johnson said.

“Of course.”

“Do you believe in the baptism of the Holy Spirit?”

“Of course.”

“Do you practice gifts of the Spirit, like healing and prophecy?”

“Of course.”

Johnson said that in the United States, those were some of the distinctive marks of Pentecostals. But maybe it was different in China. Why not use the term?

“Oh, there’s an American preacher on the radio who is beamed into China,” the Chinese Christians explained. “He’s a Pentecostal, and we’re not like him.”

Names can be tricky. What do you call a Pentecostal who isn’t called a Pentecostal? The question sounds like a riddle, but it’s a real challenge for scholars. They have struggled for years to settle on the best term for the broad and diverse movement of Christians who emphasize the individual believer’s relationship to the Holy Spirit and talk about being Spirit-filled, Spirit-baptized, or Spirit-empowered.

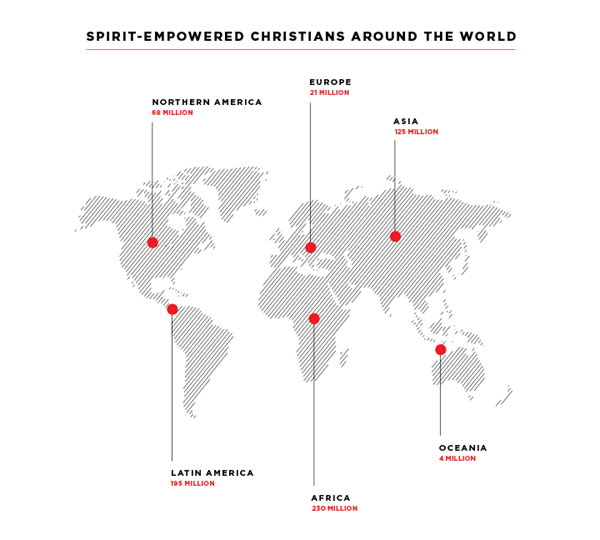

Globally, the movement includes 644 million people, about 26 percent of all Christians, according to a new report from the Center for the Study of Global Christianity. The study was done in collaboration with Oral Roberts University, named for one of the most famous Pentecostal evangelists in the 20th century, to be shared at the Empowered21 conference, featuring 70 speakers such at Bethel’s Bill Johnson and Assemblies of God leader George Wood. The conference, which was originally going to be in Jerusalem, will be held online starting Sunday.

Image: Center for the Study of Global Christianity

The report represents the first attempt at a comprehensive demographic analysis of this group of Christians in almost 20 years. These findings will be widely cited by scholars and journalists seeking to understand these Christians, especially as they impact places like Qatar, Cambodia, and Burkina Faso, where their numbers are growing fastest, and places like Zimbabwe, Brazil, and Guatemala, where they now account for more than half of all Christians.

In the debate over what to call the movement—which has been dubbed “global Pentecostalism,” “Pentecostal/Charismatic,” and “renewalist”— Todd Johnson and his co-author and co-director Gina Zurlo propose another option: Spirit-empowered Christianity.

“The name has been a perennial problem,” Johnson told Christianity Today. “One of the first things we asked is what is it that is common with all these groups. It turned out to be the baptism of the Holy Spirit. People talk about being filled with the Holy Spirit and an older term is ‘Spirit-filled.’ But a lot of groups have emphasized being empowered.”

Like the Chinese Christians noted, “Pentecostal” is associated with American churches, Johnson said, such as the Assemblies of God and the Church of God in Christ. The term indicates a connection to the multiracial Azusa Street revival in Los Angeles in 1906, where the Los Angeles Times reported a “new sect of fanatics is breaking loose” with a “weird babel of tongues.” The term “Charismatic” is connected to a renewal movement starting in the 1960s and ’70s, where Christians received the baptism of the Holy Spirit but mostly stayed in their own denominations—especially Anglican and Catholic churches.

But there are lots of other groups that are independent of major denominations and disconnected from the American history of Azusa Street. They also emphasize the empowerment of the Holy Spirit and the importance of the experience of Spirit baptism, but they’re not really “Charismatic” or “Pentecostal” in the same way.

Image: Center for the Study of Global Christianity

“Asking groups, ‘Do you believe or practice the baptism of the Holy Spirit?’ that was a really good question to ask,” Johnson said. “What we found in the end is that the baptism question gets at the commonality.”

Not all scholars are convinced by this new term. Some don’t even think a single name can work for a movement so diverse.

“It’s tough to nail Jell-O to the wall,” said Daniel Ramírez, professor of religion at Claremont Graduate University and author of Migrating Faith: Pentecostalism in the United States and Mexico in the Twentieth Century.

Ramírez said that part of the power of Pentecostalism has always been that people can take it and make it their own. It is endlessly adaptable, portable, and regenerative. An indigenous Mexican man, for example, received the gift of the Holy Spirit at the Azusa Street revival and was recorded through a translator thanking the people at that church. But then he left, Ramírez said, and no one at Azusa Street had any control over his theology or authority over how he shared that religious experience with others.

“That’s part of what makes it interesting,” said Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, professor of religious studies at Azusa Pacific University and author of Pentecostals in America. “It’s been diverse from the beginning. You look for a catchall term that’s vague and broad, and I use ‘Pentecostal’ to glue it back to the origins, but then I want people to think twice about the origins of the movement. Pentecostalism didn’t start in one place, whether it’s Azusa Street or a revival in Wales or in India, and so it’s always diverse.”

A single name can also imply that different Christians are more closely associated than they really are, argues Anthea Butler, a professor of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Women in the Church of God in Christ.

Lumping people together across traditions and cultures, you risk obscuring the historical and theological differences between a Catholic group that speaks in tongues, a Vineyard Church that practices holy laughter, and a Celestial Church of Christ that emphasizes purity and prophecy.

Image: Center for the Study of Global Christianity

“You say ‘Spirit-empowered’ and an old-time Pentecostal would say ‘Well that Spirit could be a demon,’” Butler said. “And nobody’s going to invite a Catholic priest over to a Charismatic church in Nigeria unless it’s for an exorcism. You can’t just compress the theological differences and flatten out the history.”

The Empowered21 conference, which begins this Sunday on Pentecost, has adopted the “Spirit-empowered” label. Some of the breadth of the movement is reflected in the conference lineup alone: American evangelicals like megachurch pastor Chris Hodges and Hobby Lobby board chair Mart Green are sharing a virtual stage with Cindy Jacobs, part of the New Apostolic Reformation, and Todd White, a Word of Faith preacher, in addition to leaders from Asia and Africa.

Any term is going to bring some people together and drive a wedge between others, according to Cecil M. Robeck, professor of church history at Fuller Theological Seminary. Robeck has been a part of ecumenical dialogues since 1984 and thinks the term “Spirit-empowered Christian” could help some believers see what they have in common. But it also might throw up walls where they don’t need to exist.

“I worry about line-drawing,” Robeck said. “I want to know: Do we have an ecumenical future together? I want people to experience the Holy Spirit, but I don’t want to say they have to jump another hurdle to talk to me.”

Johnson is unfazed by the criticism. He doesn’t think “Spirit-empowered Christian” is a perfect term, but he will argue “it’s as good as any.”

“We used ‘renewalist’ for a while,” Johnson said, “but we decided that’s a neologism, and we thought, ‘Well, we want to use something more natural.’ … If you’re trying to get at what all these groups have in common, ‘empowerment’ isn’t a bad choice, but it’s also not the only one.”

The new study, Introducing Spirit-Empowered Christianity, will be widely available in September. It predicts that by 2050, the numbers of Spirit-empowered Christians will grow to over 1 billion, which will be about 30 percent of all Christians. But when nearly one out of every three Christians practices Spirit baptism, scholars will likely still debate what to call them.

“This argument is always going on,” said Nimi Wariboko, a Pentecostal theologian at Boston University. “What they are trying to capture is the move of the Spirit. Americans often want a term that reminds people of the umbilical cord to the West. But the essence is not geographical origin. The essence is not history and the essence is not doctrine and the essence is not the numbers. It’s the Spirit. And the Spirit moves.”

No comments:

Post a Comment